TL;DR: A newly analyzed Viking silver hoard from Bedale (North Yorkshire) shows that Viking-Age wealth in England flowed not only from raids but also from long-distance trade, including silver dirhams minted in the Islamic world. Using lead-isotope and trace-element testing, researchers tied parts of the hoard to Western European coinage and to Middle Eastern sources, confirming a dual-currency economy in the Danelaw where weighed bullion and coin circulated side by side.

Why this Viking silver hoard matters now

Every few years, a discovery shifts how we talk about Vikings. The Bedale hoard—found in 2012 near the market town of Bedale—just did that again. The latest peer-reviewed study in Archaeometry applied lead-isotope and trace-element analysis to Bedale’s silver ingots and jewelry. The results point to three source streams: Western European coinage, Islamic dirhams, and blends of both—a fingerprint of exchange stretching from the Abbasid Caliphate to North Yorkshire.

Why it matters for numismatists and investors: source-provenance evidence moves us beyond the “Vikings as raiders only” cliché into a documented system where silver flowed along Eurasian trade corridors and was repurposed into bullion, ingots, and ornaments. That’s a richer (and more accurate) framework for valuation, attribution, and collecting.

“The Vikings weren’t only extracting wealth from the local population—they were also bringing wealth with them when they raided and settled,” notes the University of Oxford team behind the study. Their tests link several Bedale ingots directly to Islamic dirhams while confirming a Western European component from Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian coinage.

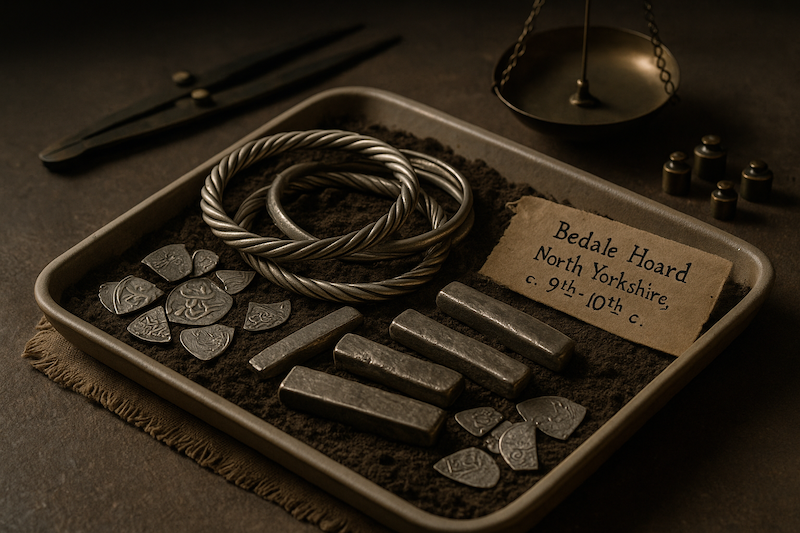

What was in the Bedale hoard?

Discovered by responsible finders and subsequently conserved and displayed, the Bedale hoard dates to the late 9th–early 10th century. It includes 29 silver ingots, ornate neck rings, arm rings, and a gold-adorned sword pommel—iconic items of value and status in the Viking world. The ensemble is now well documented by Yorkshire museum sources and recent science coverage.

- Find context & public display: Found in 2012; acquired and exhibited by the Yorkshire Museum after conservation.

- Composition: Dominated by silver ingots (the backbone of a bullion economy), with jewelry and prestige objects that could be worn, traded, or cut down into hacksilver as needed.

The Viking “bullion + coin” system (and why it matters for value)

If you collect Viking-Age material, you’ve met two parallel systems:

- Weighed silver (bullion)—ingots, bars, chopped ornaments (hacksilver), valued by weight and fineness;

- Coin—Anglo-Saxon and later Viking-minted pieces in the Danelaw.

This dual-currency economy is attested widely by finds and scholarship: bullion and coin co-circulated between c. AD 865–940, with standardized weights and balances enabling fair exchange. The Bedale science reinforces that model by showing bullion made from melted coins of different origins and silver refined with local lead.

For pricing and authentication, that means two things:

- Metal provenance (not just style) can be diagnostic;

- Blended sources are normal, not suspicious, for Viking-Age bullion.

How dirhams reached England: routes and reach

To modern eyes, Islamic dirhams in a North Yorkshire hoard look exotic. To Vikings, they were opportunity. The Austrvegr (eastern route) up the Volga and across what’s now Russia connected Scandinavia to the Islamic world; dirhams travelled as payment for furs, slaves, and high-value goods before being chopped, melted, or re-cast in workshops from Scandinavia to Jórvík (Viking York). Bedale’s science confirms that chain archaeometrically.

And Jórvík was no backwater: archaeological syntheses describe it as a bustling trading hub with links spanning the Caspian and Black Seas to the North Atlantic. That economic gravity helps explain why Eastern silver ends up in Northern England.

The Viking silver hoard and Jórvík (Scandinavian York)

York (Jórvík) sat at the heart of the Danelaw and functioned as a manufacturing and distribution center. Finished goods moved out; exotic raw materials and coins moved in. The Bedale hoard aligns chronologically with this phase, illustrating how regional workshops could blend Eastern and Western silver—and even refine with locally available lead—to produce the pieces we now study.

What the science actually did (in plain English)

The team sampled ingots and jewelry from the hoard and ran lead-isotope tests alongside trace-element measurements (think bismuth, gold, copper, etc.). Those chemical fingerprints were then compared to known mining and minting signatures. Outcome:

- A Western European component consistent with recycled Anglo-Saxon/Carolingian coinage;

- An Islamic dirham component pointing to sources around modern Iran and Iraq;

- Some mixed signatures, implying re-melting and blending in Viking-Age workshops;

- Evidence that local lead was used in refining steps, again tying the metal’s later life to England/Scandinavia.

For numismatists, this is the kind of lab work that underpins EEAT (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness): it grounds our stories about trade and money in measurable data.

A collector’s lens: how to read Bedale for buying, selling, and study

Opportunities

- Type focus: Hacksilver, ingots, and ornaments from the Viking world remain a specialized but vibrant category—especially pieces with secure provenances and published pedigrees. Bedale’s high-profile science will boost interest in comparable, documented items.

- Research dividends: Expect updated die-link and workshop discussions as geochemical findings are integrated into typologies. That can clarify attributions—and values.

Cautions

- Provenance risk: Hoard-context pieces like Bedale are typically museum-retained, not marketable. Don’t let headlines about the hoard inflate prices for unrelated items lacking documentation.

- Legal/ethical basics: In the UK, hoards fall under the Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme protocols; elsewhere, export and heritage laws apply. When buying, insist on clear, dated paperwork.

Bedale vs. other Viking hoards: what’s new?

Many famous hoards (Cuerdale, Vale of York, Silverdale) demonstrate Viking wealth, but Bedale is a standout for its geochemical resolution and the balance of bullion plus elite items. Media and museum sources highlight the hoard’s 29 ingots and elaborate neck rings; the new study adds the where the metal came from story with scientific precision.

Pros and cons (balanced view)

Pros

- Hard science meets history: Lab data nails down Eastern vs. Western silver contributions and validates the dual-currency model of the Danelaw.

- Trade-network clarity: Confirms that England sat inside a pan-Eurasian economy, not just a raiding zone.

- Public access & scholarship: Bedale objects have been conserved and displayed, inviting broader study.

Cons / Risks

- Over-generalization: One hoard doesn’t rewrite every local economy; it’s a powerful data point within a bigger corpus.

- Market misreads: Hoard publicity can spill into price bubbles for unrelated items—buyers should separate museum pieces from market specimens.

- Forgery pressure: As interest in Eastern-linked bullion rises, so does incentive for fakes; rely on published comparanda, reputable sellers, and where relevant, non-destructive testing.

The Viking silver hoard in economic context: coin vs. bullion (side-by-side)

| Feature | Coin economy (Anglo-Saxon/Viking mints) | Bullion economy (weighed silver) |

|---|---|---|

| Unit of value | Denomination & authority | Weight & fineness |

| Typical forms | Pennies, later Viking issues | Ingots, arm rings, hacksilver |

| Verification | Legends, dies, mint standards | Weighing on scales; sometimes touchstone |

| Source silver | Local/Western mints | Mixed—Western coins + Eastern dirhams |

| Where attested | Towns, markets, tax | Hoards, workshops, “pay on weight” contexts |

| Evidence base | Coin finds, dies, law codes | Ingots, chopped ornaments, weight sets, science |

| Sources: Danelaw research on dual currencies; Bedale geochemical study for mixed sources. |

Case study: Jórvík’s role in turning coins into bullion

Contemporary syntheses on York emphasize manufacture and trade, not just garrison life. The Bedale signatures of mixed silver and local lead refining line up with a picture of regional metalworking: imported coin fed into furnaces; outputs emerged as standardized ingots and ornaments used as currency and display. In other words, Jórvík added value—a detail collectors love when tracing workshop styles and techniques.

FAQs

What exactly ties Bedale to the Islamic world?

Lead-isotope and trace-element matches on nine ingots point to dirham-derived silver minted under the Islamic Caliphate (regions of modern Iran and Iraq).

Was most of the hoard “Eastern”?

No. The study found three streams: Western European coinage, Islamic dirhams, and mixed metal. Western sources remain substantial; the significance is the proven Eastern component.

What dates does the hoard belong to?

Late 9th to early 10th century, aligning with Viking Jórvík and the Danelaw’s bullion + coin phase.

Where can I see it?

At the Yorkshire Museum (York), which has conserved and exhibited the hoard. Check their updates for current display status.

How does this change collecting?

Expect tighter provenance scrutiny and more interest in scientifically tested items. For market pieces, prioritize documented pedigrees; for study, follow forthcoming publications from the Bedale team.

Bottom line (and a collector-friendly call-to-action)

The Bedale Viking silver hoard turns a global spotlight on a regional find—and gives collectors a model for how science, history, and the market can work together. Silver didn’t just arrive in Britain by sword; it came by scale and contract, carried along routes that connected York to Baghdad’s sphere. For anyone building a Viking collection, the message is clear: follow the evidence chain—from lab signatures to museum records—and let that rigor guide your acquisitions.

Action step: Read the Archaeometry paper’s summary, scan the Oxford release for key quotes, and—if you’re shopping—favor pieces with documented provenance and, where possible, published analysis. Then plan a trip (or virtual visit) to the Yorkshire Museum to see how this research looks in the case.